Addressing the shortfall in mental health capacity

As the need for capacity in mental health increases, we look at the challenges involved in ensuring we have the right infrastructure in the right places.

In June 2024, a report was published by the British Medical Association (BMA) titled, “It’s broken”: Doctors’ experiences on the frontline of a failing mental healthcare system. The report consolidated in-depth interviews with doctors across the mental health system, exploring their experiences of providing mental healthcare, including what helps and hinders them in providing good care to patients.

In the paper were some alarming findings. We wanted to explore these further with a view to understanding if good healthcare design could support the NHS in tackling the challenges highlighted. To do this we gathered a diverse panel of experts in mental health to participate in a collaborative workshop to discuss the key points raised. This included experts by lived experience, experts in developing and managing estates, experts in managing mental health services, and colleagues in design and financial modelling.

From this workshop, we developed a collaborative output of ideas and recommendations which were presented to sector colleagues and peers at the Design in Mental Health Conference in June 2025. Here, we will summarise the main findings of the report and the recommendations in our design-led response.

The attendees of our collaborative workshop.

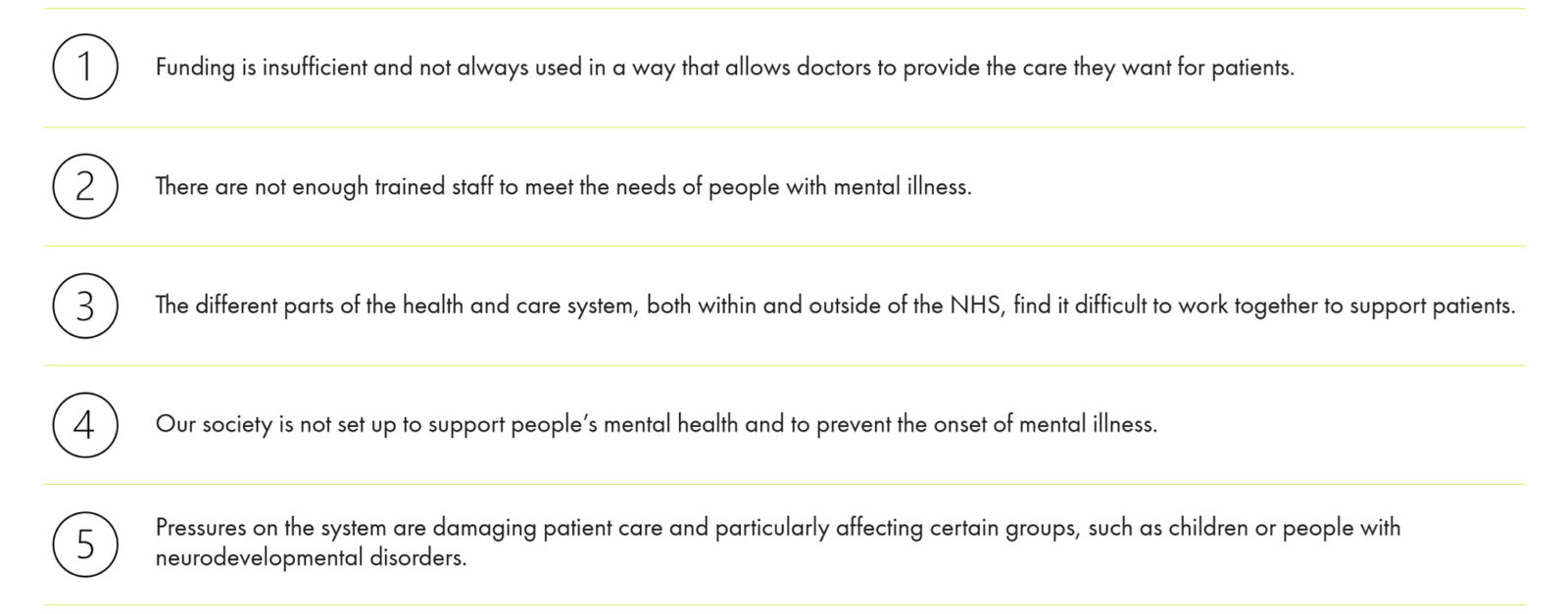

The report highlights five key challenges from funding and staffing, to collaboration and social pressures.

The five factors identified in the report that summarise the challenges facing mental healthcare provision.

Amongst the most revealing insights included a 48% increase in mental health referrals in the last 10 years against a 21% decrease in available beds, leading to a growing strain on resources. In response, funding provision has been insufficient in addressing this imbalance, leading to negative impacts on care quality and staff morale. Consequently, over 25% of service users wait over 12 weeks to receive mental health care.

Figures also highlight a shortage of trained and experienced mental health professionals, with the level of job vacancies in mental health, far exceeding the NHS average, particularly in the most qualified roles.

The report also highlights the multiple touchpoints in the health system that patients initially present with mental health concerns and a perceived lack of interoperability and collaboration between organisations. Currently, around 40% of GP appointments are for mental health related issues, compared to less than 3% of emergency department attendances. Although, it is noted those attending an emergency department with a mental health related issue are twice as likely to spend over 12 hours there, compared with a patient receiving treatment for a physical condition.

Finally, the significance of social determinants in preventing the onset of mental illness is highlighted by the report. It states that the 22% of the population in poverty are 2 times more likely to develop a mental health condition. If we accept that prevention is better than cure for long term health outcomes, it is telling that there has been a 20% decrease in local authority public health grants for initiatives such as weight loss and smoking cessation.

Mental healthcare in this country is dysfunctional. It’s broken.

To begin our discussion, we asked our experts to give their immediate reaction to the report’s headline quote, shown above. You can scroll through a summary of the comments below.

On the whole, the comments reflect a view that mental healthcare certainly has its challenges and could be operating more effectively, but that there is a lot of good work being done throughout the system to the benefit of those receiving care. The term ‘functionally dysfunctional’ seemed to provide a better characterisation, with a view that with more adequate funding and the right strategic focus, the sector could solve many of its existing problems, and become a standout example of good practice internationally.

In summarising the output of the workshop, we have grouped the main talking points and recommendations into a six point manifesto, which we believe provides a design-led response to the challenges facing the sector. We will briefly look at each in turn.

Our six point design-led manifesto.

It is unlikely that funding will increase significantly, so long term strategic planning is needed to inform decision making and to ensure equality of quality.

There was frustration amongst the group regarding the often-hasty business case process, which can be far from strategic, with submissions expected hastily and reactively. With a more strategic focus there is greater opportunity to have infrastructure solutions that are adequately considered, and therefore ‘oven-ready’ when funding does become available.

There was recognition that for Trusts to be strategic, the NHS at a higher-level needs to do the same, with agreement of priorities across political parties to avoid unproductive short-term policy decisions for political point-scoring. Plans should also provide the flexibility to balance national priorities with the ability for local priorities to be funded where there is an urgent need.

Consideration must also be given to the future role of ICB’s, and whether they should be allowed a greater role in strategic commissioning, to reduce the inequality in facilities and environments across regions.

It’s completely nuts the way we fund infrastructure in the NHS. Everybody runs around given about two weeks to produce a business case to bid for money.

We need a 10-year plan and with that, a plan for how we invest in the estate that’s then supported cross party and isn’t used as a political weapon.

At a micro-level it was recognised that large disparities in the quality of accommodation currently exists even within each estate, with mixtures of very good and very poor facilities often occurring side-by-side. Here, it is important to understand the strategic value of large capital investments in new build facilities versus the reuse and improvement of the existing building stock (i.e. to reuse or replace). Where limited funding is available, strategic estate planning provides a framework for informed decision making, ensuring value for investment.

We’re never going to be able to afford everything nice, new and shiny. Do we have to then start thinking about how we reuse the estate most effectively?

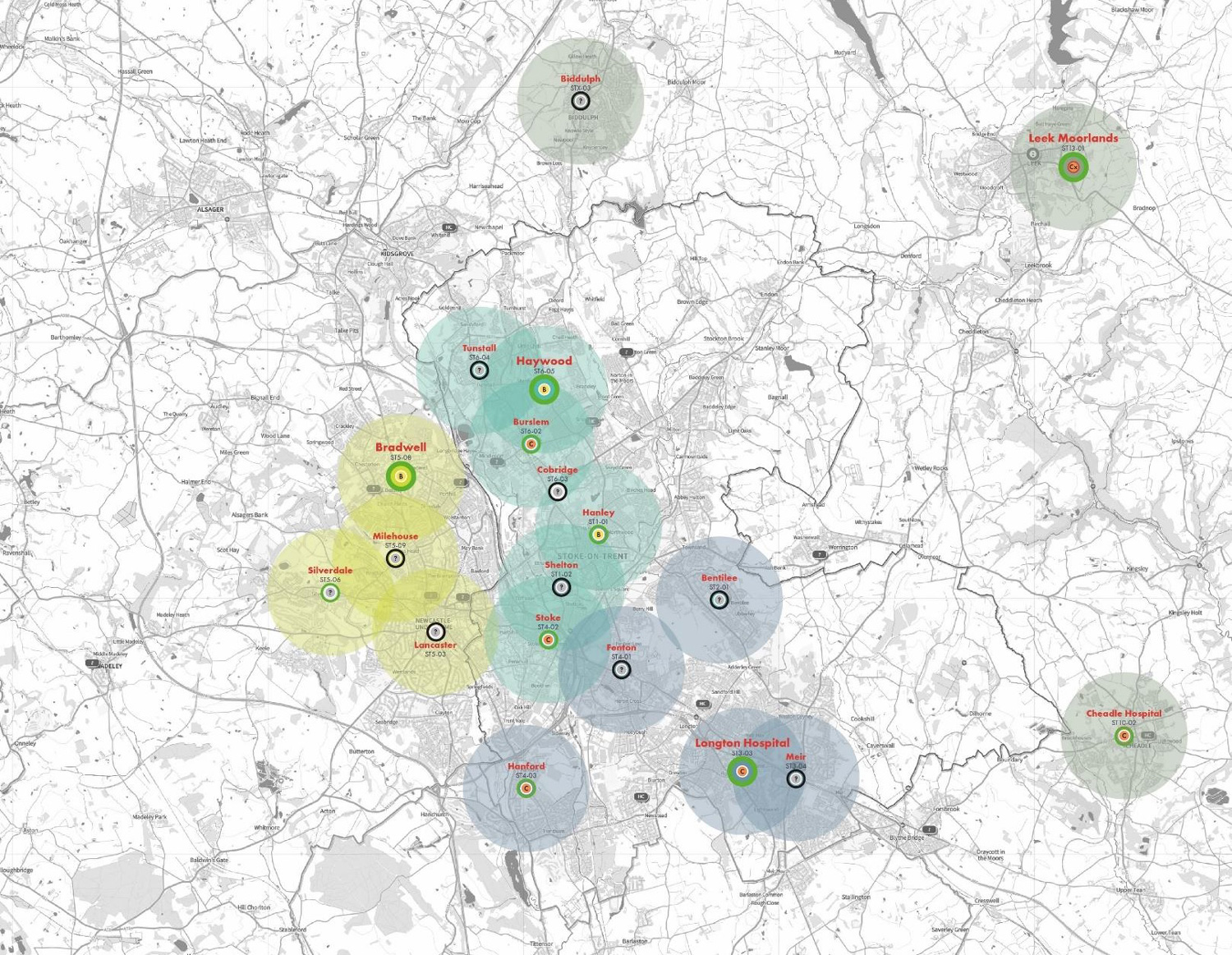

Recently, in collaboration with Midlands Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, we put this approach into practice. Following the merger of two Trusts bringing together physical community health and mental health services, we worked strategically with the resulting Trust to gain an informed view of 40 properties within the new estate.

We consolidated all the Trust’s available data sets and recast the data, assessing each site against a defined list of criteria. Scores were assigned and presented in a legible single-page dashboard for each property, allowing a high-level strategic overview of its comparative value.

Adopting a systematic approach and considering each building as part of the wider estate enabled us to support the Trust in developing a comprehensive regional estate strategy. Recommendations within the strategy included retention, retention with investment, and asset disposal to fund improvements elsewhere. Proposed investments ranged from interior refurbishment to extension and new build, depending on the local requirements and the suitability of the existing asset.

Good design doesn’t have to cost more; it can improve outcomes and ultimately save money in the long term.

Our group discussed the value of good design and what that might mean to different people, especially service users. One of our contributors with lived experience said, “I absolutely 100% became more unwell when I was admitted into hospital”, an important reminder that designing environments that are truly therapeutic is vital to recovery, and can subsequently reduce the length of stay. Of course, there is a need to understand what is really important to service users through thorough engagement and co-design processes.

From a designer’s perspective, there was concern that some of the fundamentals of mental health design (e.g. therapeutic access to nature, natural light, and areas of retreat) were not being adequately protected during value engineering exercises — for example, landscape is often the first to be removed, even areas of curtain walling or windows reduced in size. More work is needed to inform clients and contractors about the long-term impact of achieving these immediate savings, and what it ultimately means for the end users.

Often of greater significance to the lifetime cost of a building is the extent to which sustainable design for adaptability has been considered. This can include maximizing flexibility through standardized ward design, offering a model that can be easily adapted for different patient cohorts as services adapt and change over time.

If I think back to my own experience … the aspects of that unit that felt healing were the trees, the natural light, the relationships, opportunities for creativity, and spaces that I could retreat to that felt comforting. I would argue that those don’t have to cost a fortune.

Sometimes to save money long term, you have to invest in something of good enough quality that it can take adaption … it’s about building everything to a certain spatial and quality standard that spaces can be converted in the future.

Completed in 2015, Clock View Hospital for Mersey Care NHS Trust provides 80 inpatient beds for Adults and Older People Mental Health and Dementia Services within five wards arranged as a series of pavilions in a landscaped setting. The classic courtyard model was adopted with single sided corridors, maximizing natural light and views to nature.

Each patient has their own private bedroom with ensuite and 24-hour access to shared therapeutic activity facilities within each ward. Each ward has its own accessible, secure private garden. The interior design features warm colour themes and natural wood finishes which are warm to touch. Patients and staff enjoy a range of integrated art and sculpture which were commissioned through a partnership with Tate Liverpool. A simple building, but one that valued the therapeutic properties of blending architecture, landscape design, interior design, and art.

Clock View Hospital received the Design for Sustainable Development Award at the European Healthcare Design Awards 2023, an award recognising an exemplar healthcare project that has demonstrated flexibility and high performance over time.

A focus on designing for staff needs as well as patient’s needs benefits everyone and supports quality care.

Digging into the issue of staff shortages, the group discussed the role that facility design can and should play in meeting this challenge. It was felt that it is difficult to tailor ward designs to accommodate reduced staffing without negatively affecting the patient environment. We heard from our participants with lived experience that their interactions and relationships with staff members were integral to their recovery journey and that they could sense when staff were stretched, unhappy or feeling burnt out. It was felt that the focus should be on the design of facilities that provide a positive environment for staff, ensuring that they feel valued and supported. Ultimately, this will support the ability to recruit and retain staff, whilst having the benefit of improving the quality of care provided to patients.

It was felt that staff facilities are often overlooked in the stakeholder engagement process with the focus of time being largely apportioned to getting the patients facilities right. It was agreed that time should be made for better understanding of staff needs.

Whilst there are some obvious provisions in terms of staff respite and welfare accommodation, the group also thought that we shouldn’t overlook some of the more basic design moves which reinforce positive staff and patient relationships. The kind of interstitial spaces that allow for informal interactions and check-ins that provide a sense of continual support.

Unhappy, frustrated and burnt-out staff are inevitably going to impact on the quality of care for the patients themselves. We saw it all the time in my patient group when I was in hospital. We sensed the burnout of the staff.

I do think that some of the things that are often seen as wasted space are things that can be really conducive for [creating a therapeutic environment]. The kind of spaces where staff or service users can just pause in open environments, sit at a window, or if staff are checking on a patient, they don’t have to hover in the doorway leaning on the door frame, things that enable us to do things that we need to do as part of routine care in a way that is sensitive and as non-invasive as possible, but that also encourages the building of relationships.

From a designer’s perspective, we feel we have come a long way in designing for better mental health – moving away from double loaded corridors and staff being condensed around a nurse base, to a more relational model where staff aren’t working in a pressure-cooker environment. But we do need to be careful with regards to the evaluation of value versus cost, and the impact this can have for both the staff and patient experience if we start moving backwards in our thinking.

Kimmeridge Court has been crafted to create a private and therapeutic environment for the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Through close consultation with clinical staff, the facilities have been specially designed to enable patients to re-establish a positive relationship with food and exercise.

A key consideration for the design was ensuring that staff had an effective environment for the delivery of care with the ability to foster relationships with patients built on trust. We talked about the benefits of relational security and the way design can facilitate chance meetings between staff and patients. Generously sized corridors throughout the building are designed as an additional room, providing informal places to sit, rest and speak with other patients and the clinical team. These places are highlighted and enhanced by feature windows and rooflights, to create moments of joy in the day, harnessing the therapeutic nature of the building’s woodland setting.

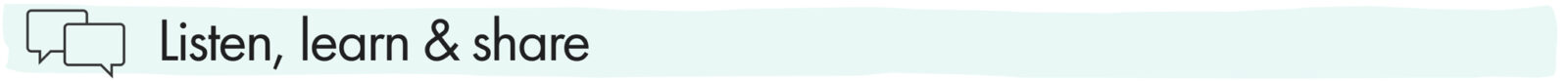

Allow time in projects for proper briefing and stakeholder engagement, and learn from the wider network, especially those with lived experience.

Consistent themes throughout our response to the challenges set out in the report, were the value of stakeholder engagement and coproduction during a project, and proper evaluation and knowledge sharing afterwards.

There are often pressures to work quickly and to meet challenging programmes, often linked to funding deadlines or cost constraints. However, we must prioritise time to listen to and learn from stakeholders to ensure that project teams are adequately briefed and informed during the design process. Gaining enough time from staff to ensure they can provide quality input can be challenging, but we must invest in protected time to ensure they can contribute properly to the process and not feel like it’s an extra to squeeze into their day job.

The discussion highlighted that some stakeholders aren’t always aware of what will benefit them the most, and it is not until they see alternative options that the art of the possible is understood. We must therefore learn from the experiences of the wider mental health design network and other healthcare organisations that have solved similar challenges, through the sharing of examples of good practice.

Particularly, harnessing the value of those with lived experience is of vital importance. No one understands the impact that environments can have on the journey to recovery better than those that have experienced this first-hand, and the skills that are developed along the way can serve many useful purposes in both the design of facilities and the delivery of services.

We design things and we do projects, at too fast a pace to get the building built on site, and we don’t spend enough time getting some of this correct. Part of that is having the staff’s time to input into the design schemes.

Asking staff what would help them in terms of their environment, the things that actually benefit them, they aren’t necessarily aware of at the point that you’re doing the design to be able to articulate them. So, it’s being able to tap into other people from other trusts that have been through a design experience and have a new environment, for them to be able to share.

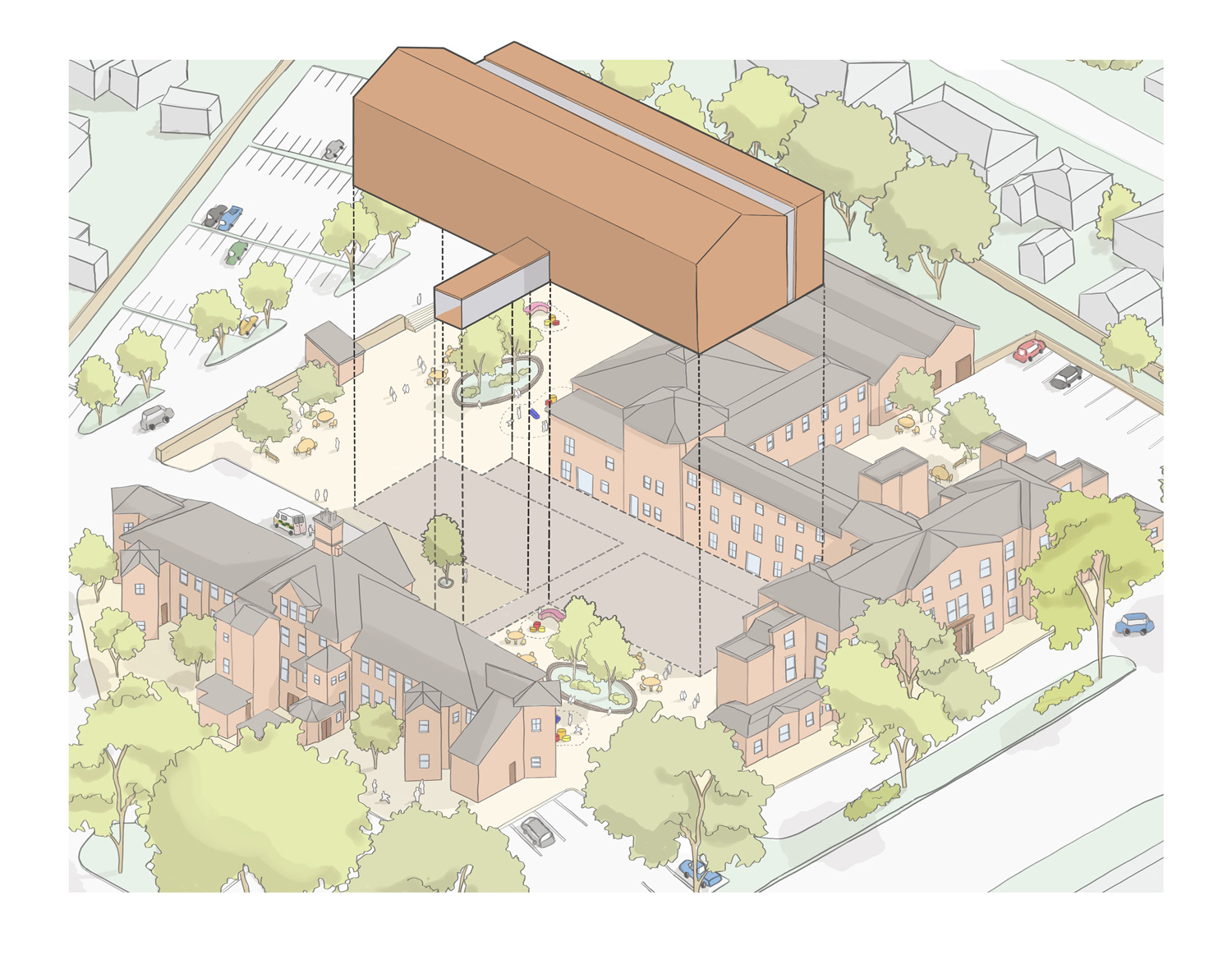

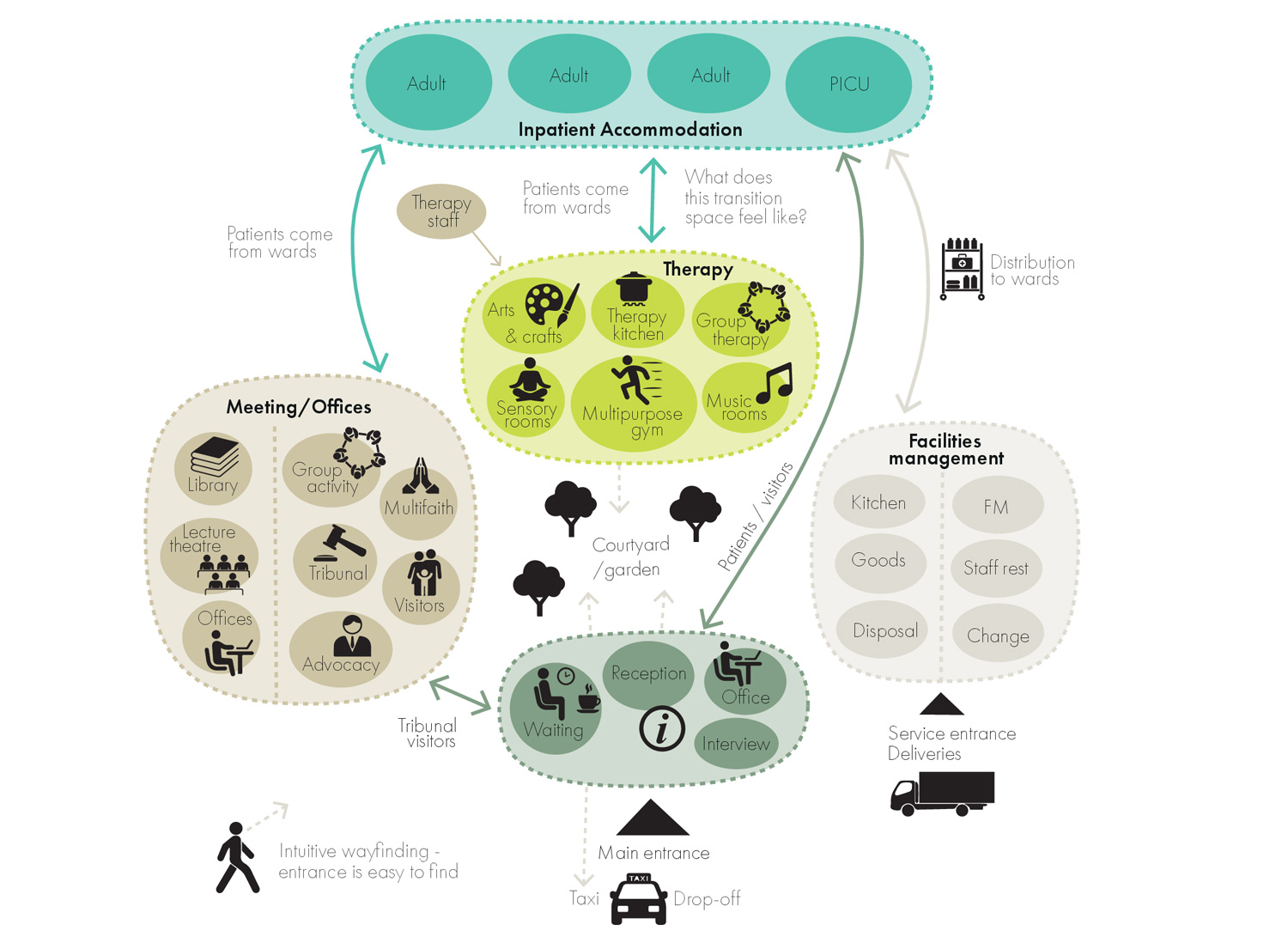

East London Mental Health Foundation Trust is reconfiguring its existing inpatient mental services to provide care closer to the population it serves. With affordability challenges, the schedule of accommodation required careful development, to optimize every square metre. The Trust has involved former service users throughout the design process, from the selection of the design team, to building the brief and assessing design proposals. A joint team of staff, former service users and the architect visited existing facilities and exemplar buildings. We interviewed staff, reviewed the spaces and layout, and evaluated together what worked well, what did not, and how to improve.

Crucially, there was a protected period for staff to take part in the site visits and resulting co-production, time that was planned well and paid for, rather than an expectation it would be done through goodwill. This greatly increased the value of the engagement process.

Learn from successful models of integration to provide more holistic and preventative care, and design buildings that support collaboration.

Our group was in agreement that greater collaboration between health organisations is needed to provide more integrated services, where patients are treated as a whole person and not several compartmentalised challenges. This represents a more relational way of delivering mental health care, as opposed to transactional responses to individual issues. One of our participants shared a comparison to being treated by cancer services, where treatment was fully holistic, from day one on the pathway, an experience that is worlds away from their experience of mental health services.

Innovative international models of care were discussed as potential sources of inspiration for a more relational approach, including the Trieste model in Italy. The Trieste model originated in the 1970s under psychiatrist Franco Basaglia, and it revolutionized mental health care by transitioning from institutionalisation to community-based services. It emphasises holistic, person-centered care, integrating individuals with mental health conditions into society (see accompanying case study).

We know it works, but it does feel that implementing it in the UK has a way to go yet. For it to work here, we need to plan – the strategic point again – for integration and holistic care. It isn’t enough to combine services in a building and expect collaborative working to flourish, we need to plan how services should integrate and what that means for the patient journey and building design.

The NHS 10 Year Health Plan and a shift to a ‘Neighbourhood Health Service’ provides a positive indication of future plans. As does the first batch of 24/7 neighbourhood mental health centres which are being rolled out across the country. But the detail around implementation is important, as is sufficient funding to ensure success. However, examples such as the Trieste model show that new models of service delivery can achieve long term cost savings if prioritised.

I think for the patient, the person at the heart of this, they want to just feel like they’re being seen as a whole person … you can end up feeling like different parts of your challenge are being compartmentalised.

I genuinely am hopeful that the next iteration of neighbourhood working is going to start bringing organisations together, and that will ultimately lead to better integrated working, more efficiency with our resources, and most importantly, better experiences and outcomes for our service users.

The Trieste Model operates through Community Mental Health Centers, small facilities with 6–8 beds, open 24/7, and providing immediate, walk-in access without referrals. These facilities have no locked doors, promoting freedom and dignity. The model provides integrated services with multidisciplinary teams and social cooperatives: aiding social reintegration.

Some of the recording outcomes are remarkable.

The World Health Organization recognizes the Trieste model as a benchmark for community-based mental health care, influencing reforms in over 40 countries and very much valuing the role of care coordinators.

Images from the Mental Health & Social Justice Network

Just over 7 years ago in Hull, we designed the Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre. Whilst it is not a mental health facility — it was for older adults with chronic needs — it demonstrates the importance of building design in fostering an integrated, person-focused approach to healthcare delivery. The building brings together a number of services into an integrated hub, promoting joined-up delivery, whilst also accommodating a new fire station for Humberside Fire and Rescue. This move recognized the increasing role the fire and rescue service plays in assisting the NHS as the first responder for slips, trips, and falls in the home.

It was very much the idea of a fully integrated model of NHS and social care and voluntary sector assessment and treatment under one roof, and the building design facilitated a clockwise route for the patient journey, with the heart of the building being the social hub where everyone comes together. Patients may spend an entire day at the centre and the nature of the facilities reflect this extended visit. This includes a café run by Inspire Hull, a charity which aims to improve physical and mental wellbeing. Here, activities are curated which bring people together to tackle feelings of social isolation.

Like the Trieste model, the building now has a range of measurable outcomes. A study, led by researchers from the Wolfson Palliative Care Research Centre at the University of Hull, found that for the frail cohort of patients who had more than five ED attends in the twelve months preceding assessment at the centre, there is consistently over 50% reduction in emergency department attends and admissions in the following twelve months. The building provides valuable lessons for similar models adapted for mental health care.

Provide more accessible touch points in communities for therapeutic conversations and support for the determinants of poor mental health.

Our final manifesto item is about making services accessible for all, where people need them, and perhaps more importantly, where people want them. Feedback from historical research conducted by members of our group suggests that many people would prefer to be seen in their own home — or a local, more informal setting — than a traditional mental health facility.

At the same time, we know that there are social determinants that make some people more likely to require mental health support than others, particularly those facing financial challenges. This begs the question as to why more preventative approaches are not being used to address some of these issues before a point is reached that treatment is required at an inpatient facility? Ultimately, this would reduce demand for reactive services and the need to invest in facilities that provide this capacity.

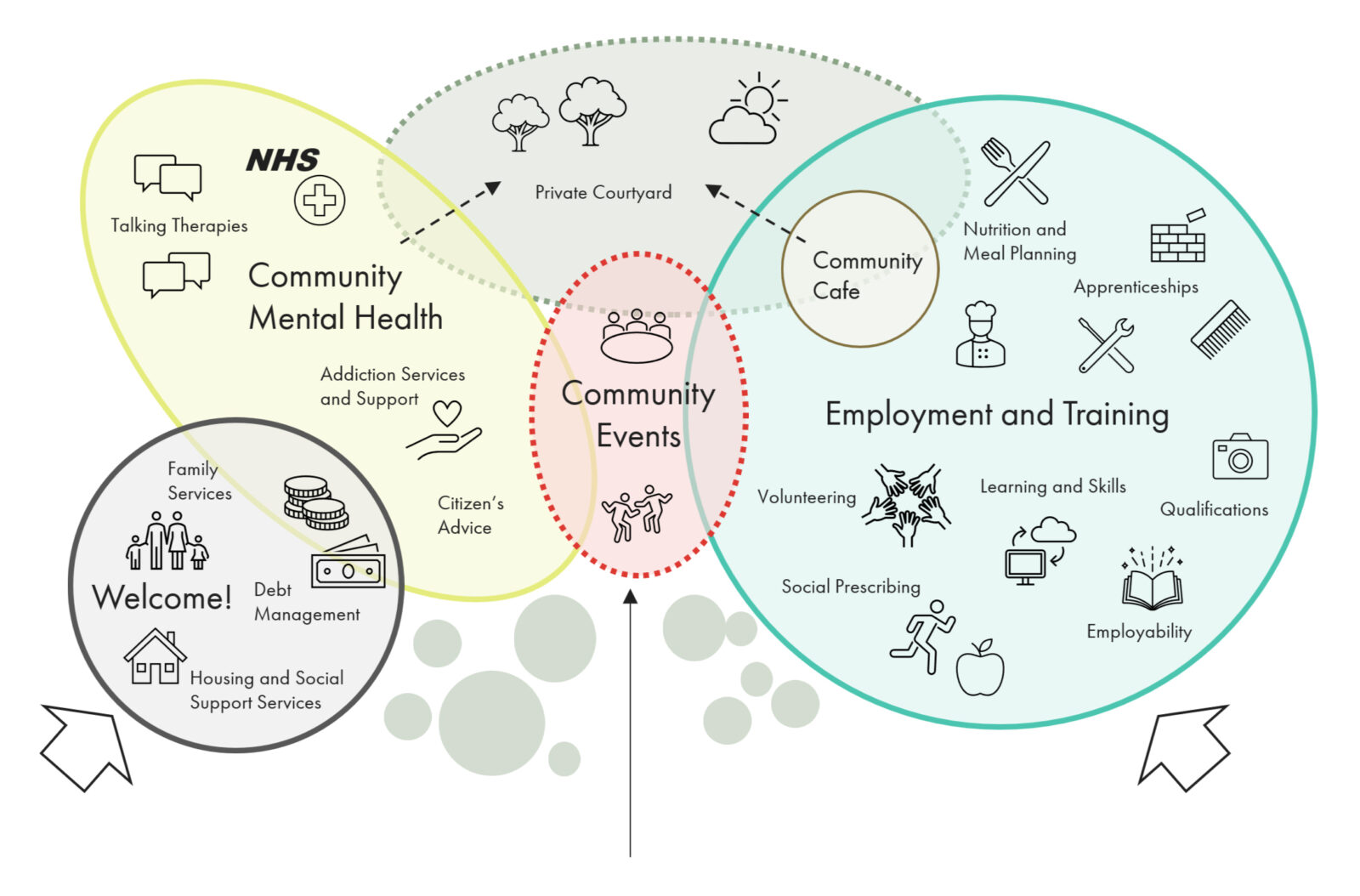

Our group discussed alternative approaches. This included smaller community-based facilities which provide access to therapeutic interactions, utilising individuals with lived experience that have the skills and tools to manage moments of crisis alongside mental health professionals. A preventative approach must be the priority, integrating mental health services with other public sector and voluntary sector services that provide support for the determinants of poor mental health, whether that be support for issues of debt, housing, addiction or social isolation, amongst others. We are seeing some examples of this, generally led by local authorities in partnership with local NHS Trusts, but again, it’s patchy and not well funded. A more focused approach is needed.

You have individuals who are struggling on a given day and feel like their only recourse is to potentially take themselves to A&E or to refer themselves back to services, or to make a GP appointment, because there isn’t that opportunity to just have a conversation that is going to potentially bring them back on track.

What fascinated me was this sense of social determinants, that some people are destined to have contact with mental health services more than others. Is there enough done when people do come into contact with care? Do you have access to additional advice, such as dealing with debt?

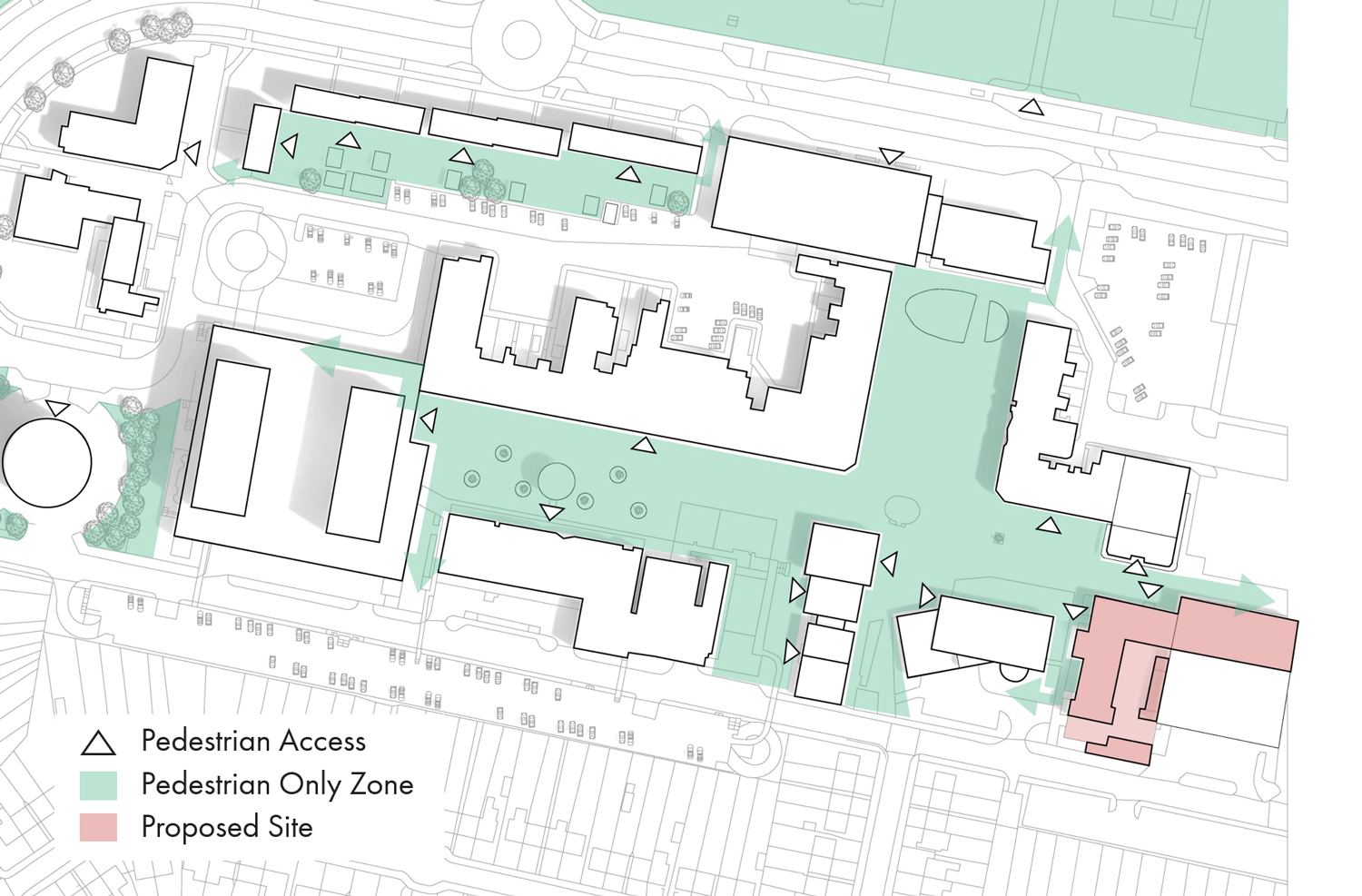

This example in the North East of England is a town centre public sector hub anchored by a community mental health service, but co-located and integrated with a wellbeing and employment hub, a citizen’s advice service, local authority services, a local adult learning college, and debt services.

Realising the opportunities presented by the health on the highstreet model, the facility benefits from a shop front in the middle of the town centre, ensuring accessibility for all ages.

The facilities enable members of the public to walk in during a mental health crisis and be taken immediately into a discreet room to receive support. Services are then immediately available to help address some of the underlying challenges that may have contributed. Ideally, for others, the proactive nature of the assistance means that their mental health will have been supported in a way that prevents a crisis from occurring.

An accessible town centre location is proposed for the public sector hub

A diverse mix of potential services have been considered to provide support for the determinants of poor mental health

At the start of the workshop, there felt like there was a consensus that the mental healthcare in this country isn’t broken, but it’s certainly dysfunctional, or functionally dysfunctional. Many staff and teams are doing great work, but they are frustrated from delivering great care in a system that is not joined up, or as efficient as it should be.

We discussed the findings of the report, and reviewing the output we developed a six point manifesto.

Mental health may be underfunded, but we must prepare for the reality that there might never be enough funding available to do all that we wish we could. We must be smarter with the money we have access to. We must be more strategic and ensure that investment is prioritised where the greatest value can be achieved in the long term.

We must promote the value of good design and find ways to demonstrate this clearly, so that we can continue to deliver environments that promote the wellbeing of both patients and staff. Longevity through flexibility and adaptability are key to securing long term value on investment.

We must allow sufficient time for planning and stakeholder engagement, particularly utilising the insight of those with lived experience, to ensure that we start on the right track and stay there throughout the process.

Finally, we must be more joined up in our thinking, and promote the value of collaboration and integration across NHS services, as well as looking to new models which focus on a more preventative approach to mental health in accessible locations. Understanding the determinants of mental health and integrating services across the NHS, public sector, and voluntary sector to help address these, will ultimately relieve strain on the system and improve population health.

As the need for capacity in mental health increases, we look at the challenges involved in ensuring we have the right infrastructure in the right places.