Designing for the health of coastal communities

We explore the ways an integrated model of care can be used to address the complex health needs of coastal towns.

Christopher Shaw | Consultant, Medical Architecture

Martin Rooney | Delivery Director, New Hospital Programme, NHS England

Jaime Bishop | Director, Fleet Architects / Architect, Health Spaces / Co-chair, Architects for Health

Stephanie Williamson | Co-chair, Architects for Health

John Kelly | Director, Lexica

Lianne Knotts | Director, Medical Architecture

The central principles behind integrated care have been around for a very long time, with multidisciplinary care initiatives and partnership working featuring in NHS policy as far back as the 1960s and 70s. Since then, integration has featured prominently in ambitions to create a more connected and collaborative health service with a patient-centred focus for the delivery of care. This has gained momentum in the last fifteen years with widespread recognition of the opportunities that integrated care can offer for funders, providers, and patients. Despite this level of intent, and the introduction of integrated care systems (ICS) and integrated care partnerships (ICP) to provide collective responsibility for resource and implementation of integrated care models, progress seems to be patchy and a long way from where we need to be.

We asked our panel to share their thoughts on why this was the case, the steps that we can take to accelerate the implementation of integrated models of care, and the factors that can contribute to its successful delivery.

The panel, left to right: Stephanie Williamson, John Kelly, Lianne Knotts, Jaime Bishop, Martin Rooney and Christopher Shaw. Image courtesy of Salus and European Healthcare Design Conference.

The panel recognised that integration is fundamentally a difficult task. This is particularly true for an organisation such as the NHS, where the ownership and management structure is complex and multi-headed. There are many stakeholders involved and it is difficult to instigate change when there are many different objectives to align. In the end, it comes down to the decision-making of people, who often have a tendency to resist change.

This is exacerbated in the case of integrated care by the cultural differences between the different departments that are expected to work collectively. Clinical Commissioning Groups, primary care providers, NHS Trusts, local authorities, and social care providers, all have ways of working built on greater levels of autonomy. Meshing these together can be tricky.

The panel felt that, in their experience, clinicians and healthcare staff have a desire to collaborate and they see the benefit of a patient-centred approach, however, they are often let down by a system which puts barriers in the way. At an organisational level, there can be a silo mentality, with individual departments protecting their pot of resources, whether that be income and funding, personnel, facilities, or even seemingly more trivial elements, such as access to Wi-Fi networks.

Whilst it was felt that the introduction of integrated care systems (ICS) and integrated care partnerships (ICP) signals a positive step in the right direction to enabled greater collaboration and breaking down of these silos, it was felt that the system is still complex with layers of bureaucracy that continue to hamper progress. Frequent change in government health strategy is also stifling momentum.

As well as the political and organisational challenges, successful integrated care must also overcome a wide range of geographic disparities and inequalities. Different parts of the country are characterised by diverse health and social care landscapes, and within each region, there are the same degrees of inconsistency between urban and rural locations. Challenges such as chronic illnesses, aging populations, staff shortages and funding gaps, create a unique set of circumstance at a local level which are very difficult to tackle with a one-size-fits-all approach to care.

During the redevelopment of Whitby Hospital, the local need dictated that an effective route to integrated care would be to consolidate the existing clinical accommodation to allow services to be more closely aligned, whilst freeing land on the site for contemporary extra care housing to extend the continuum of care.

In Hull, the pioneering Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre caters for the needs of an increasingly elderly population, providing out of hospital care and reducing the need for hospital admission. Adopting an entirely new way of delivering health services, the centre brings together a range of specialist services to provide a more holistic approach to health, care, and social support.

Before we look at how to address these challenges, it is useful to remind ourselves of what good integrated care should look like, and where we should be trying to get to.

The panel felt that integrated care should be a system for providing services close to local communities, where they are visible and accessible. For many, especially elderly and vulnerable patients, treatment closer to home and closer to their support network can have a significant impact on wellbeing and recovery. For many towns and rural locations, healthcare facilities form a supportive pillar at the centre of the community providing vital services and a social lifeline for older or isolated populations. Locating or retaining facilities where there are excellent public transport links and sufficient parking provision ensures access is inclusive and barrier free.

The generous public realm at The Jean Bishop Integrated Care Centre segregates traffic and parking facilities, and provides a boulevard and garden spaces, which encourage mobility and time outdoors.

The redeveloped Whitby Hospital retains integrated services at the heart of the coastal town, providing a focal point for health and wellbeing in this relatively isolated community.

Another advantage of embedding facilities within the heart of a locality, are that they are positioned close to other community services and public amenities providing opportunities for social prescribing. This proactive approach is about supporting individuals to take greater control of their own health, reducing the need for reactive care later down the line, reducing the burden on acute healthcare settings. At a direct level, this includes the referral of patients to voluntary and community sector organisations to take part in activities that support a wider view of the contributors to health and wellbeing, including volunteering, arts activities, group learning, gardening, befriending, cookery, healthy eating and a range of sports and leisure activities. At an indirect level, locating healthcare facilities in proximity to social and cultural facilities that can be independently accessed (libraries, museums, art galleries, cafes, and shops, for example), provides further opportunity to enrich the lives of individuals with the associated health benefits of activity, education, and social interaction.

As we look to find solutions to the decline in high street footfall, and whilst retail units in town and city centres remain vacant, there are interesting examples where healthcare facilities are being integrated into traditionally retail environments, to maximise the opportunity for social prescribing, whilst also having a regenerative effect on the local area.

Health on the High Street™ is an offering from Health Spaces, which supports NHS Trusts in creating clinical spaces in vacant retail and light industrial buildings. It offers a very simple solution to solve two high-profile social and economical issues that can help alleviate hospital pressures and waiting times whilst bringing footfall and life back to ailing high streets.

Regardless of its location, the ambition for any integrated care facility must be to provide a therapeutic environment for patients that supports wellbeing and recovery, whilst creating a working environment for staff that enables adaptability, fosters collaboration and advances knowledge sharing. This careful balance between patient privacy and the promotion of communication and cross-service integration, requires careful consideration, but provides an exciting opportunity to explore innovative approaches to healthcare design.

Finally, the panel recognised that truly integrated care meant that patients were looked after from end-to-end in their journey through the health service, regardless of their point of entry. This includes the notion that at any touchpoint in the system, you’ve never “come to the wrong place”. The system helps you wherever you arrive in the network and information is available to all healthcare staff to ensure that people can be quickly identified and helped to find the service or location that they need. This means digitally linked facilities with efficient flows of information, and buildings and estates which support a collaborative approach to care.

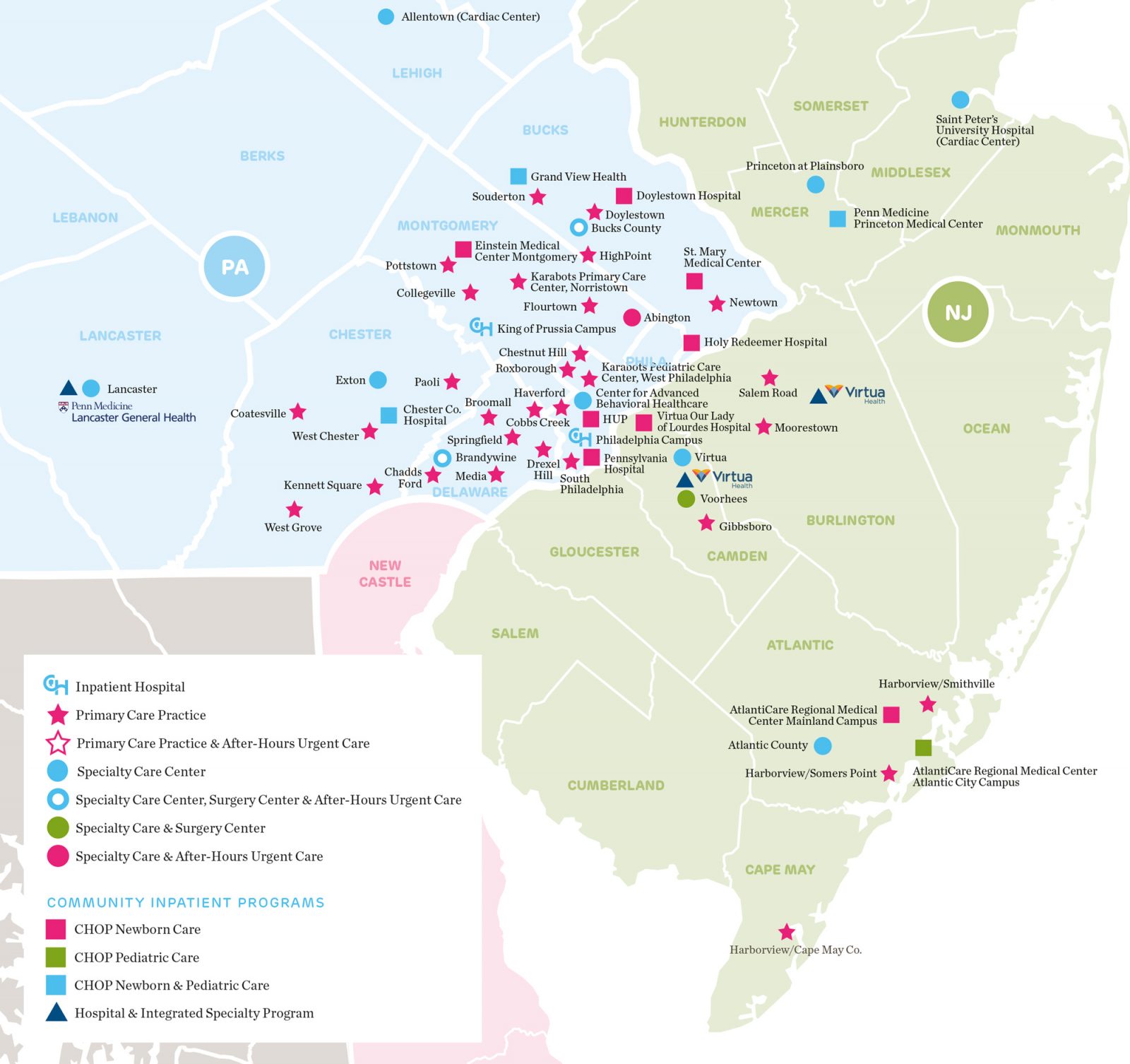

Cited as an example of good practice by the panel, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia has an integrated network of 50 paediatric health facilities providing a range of services at different scales. Anchored by two hospitals, the network includes primary care practices which provide convenient access to primary health and wellness services for children close to home, as well as urgent and specialist care facilities.

An example of therapeutic environment design with plentiful daylight, access to gardens, and the use of colour and non-institutional design to create a welcoming space.

So, if this is what we are hoping to achieve, how do we overcome the challenges to create integrated care which is more than the sum of its parts?

The panel felt that there was real reason for optimism and an opportunity to be seized. They saw potential for integrated care boards (ICB) and integrated care partnerships (ICP) to make progress if they are properly invested in and well-managed. Despite this, the pace of change needed to achieve effective levels of integration requires a system to be sufficiently agile to adapt rapidly to changing local needs. This calls for a reduction in the layers of complexity present in the current system and the removal of bureaucracy that is hampering progress. The Covid-19 pandemic is a great example of where necessity forced very rapid changes in the healthcare system with rapid digitisation, the introduction of remote appointments, the vaccine rollout, and the design and build of the Nightingale Hospitals just a few examples of fast-tracked processes which would have taken many years to complete without the added impetus. Money flows changed and funding was made available quickly where it was needed; bureaucratic processes were streamlined. A similar fundamental shift in focus would benefit the drive to integrated care.

The challenges around achieving greater integration are complex and, in many cases, the restricting behaviours are engrained. Removing the existing silo mentality and instilling a patient-focused culture, requires purposeful leadership. There needs to be a collective will to integrate, reinforced by continual education, training, and the celebration of success, when it happens. There also needs to be sufficient investment if full commitment is to be expected. Ensuring funding is available and existing money flows are protected, will increase the likelihood of buy-in.

At a more practical level, the panel felt that integrated care is most effective when a place-specific approach is employed. Experience shows that what works well in one part of the country, might not be appropriate in another. Each integrated care partnership will have a different mix of urban vs rural populations, coastal vs inland populations, different demographic and socio-economic landscapes, as well as differences to their existing estates and healthcare services. Public and stakeholder engagement will be key to understand local needs and priorities, and to bring those whose support is most needed, along for the journey. Personal involvement is a great way to overcome resistance to change.

The panel also felt that emphasis would be needed on the deployment of more sophisticated digital solutions to support collaboration, communication, data sharing, and a more efficient delivery of care. It was noted that in many areas the existing IT infrastructure falls well short of where it should for any organisation the size and complexity of the NHS. Tackling existing shortfalls must precede the next stage of technological innovation that will allow integrated care to flourish.

It has been said that in many successful integration initiatives, the role of primary care has been significantly strengthened, with patients working closely with their local GP to take a more proactive approach to their health and wellbeing, alleviating some of the instances of reactive care needed later down the line. The panel felt that a move to nationalise primary care would encourage more medical graduates into primary care and do more to retain the existing talent in the sector.

Finally, the panel discussed the need for greater availability of data in integrated care and for more academic research into the factors that determine success. There is also a need to learn by doing. An iterative process of evidence-based design will highlight the most effective routes to fostering integration. By capturing and distributing examples of best practice the global healthcare community can share an international perspective that may shed new light on this complex challenge.

We explore the ways an integrated model of care can be used to address the complex health needs of coastal towns.